How to Differentiate between Superheater and Reheater?

In the heat recovery boiler systems of combined cycle power plants and large coal-fired power plants, the superheater and reheater are undoubtedly two of the most critical heat exchange components on the steam side. For those new to boiler design, they may appear similar---both consisting of densely arranged serpentine tube bundles---and seem to have analogous functions, namely heating steam to elevate its temperature. However, from the perspective of a boiler systems engineer, these are not simply redundant components but rather independent devices with distinctly different missions and design principles. Understanding their differences is key to grasping the essence of modern, high-parameter, high-efficiency power plant design.

1. Functional Role in the Thermodynamic Cycle

From a thermodynamic cycle analysis perspective, the superheater and reheater operate at different stages of the steam expansion process and fulfill fundamentally different thermal functions.

Superheater

A fundamental component of the Rankine cycle. Its primary function is to heat saturated steam from the drum or evaporation section to the designed temperature of superheated steam.

This process significantly increases the enthalpy of the steam, enhancing its work capability. It also ensures the steam entering the high-pressure turbine cylinder has sufficient superheat, preventing condensation during the initial expansion stage and protecting the turbines flow path components from droplet erosion.

Reheater

The core equipment of the reheat cycle, specifically designed to handle steam that has already performed work in the high-pressure turbine cylinder. After expansion in the high-pressure cylinder, the pressure and temperature of this steam drop significantly, bringing it close to a saturated state. The reheaters role is to reheat this steam to a specified temperature, restoring its superheat, before it is sent to the intermediate and low-pressure cylinders for further expansion.

Core Value of Reheating

The core value of the reheating process lies in increasing the average heat absorption temperature of the cycle, thereby improving the plants net thermal efficiency. According to engineering practice data, employing a single reheat can increase unit thermal efficiency by approximately 4%–6%, while also controlling the exhaust steam moisture content from the low-pressure cylinder within a safe range (typically below 12%).

2. Design Principles and Structural Parameters

The design of superheaters and reheaters is constrained by radically different boundary conditions, which fundamentally determine their engineering design approaches.

2.1 Working Pressure

Superheater working pressure is equal to the main steam pressure of the boiler. In ultra-supercritical units, this pressure can reach 25–31 MPa. Under these high-pressure conditions, the equipment must meet stringent requirements of codes such as the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code or equivalent standards. The primary design considerations are high-temperature enduring strength and creep resistance.

Reheater working pressure is typically the exhaust pressure from the high-pressure turbine cylinder, with a standard range of 3–6 MPa—only about 20%–25% of the superheater pressure. This lower pressure requirement shifts the design focus more towards flow resistance control rather than pressure-bearing strength.

| Parameter | Superheater | Reheater |

|---|---|---|

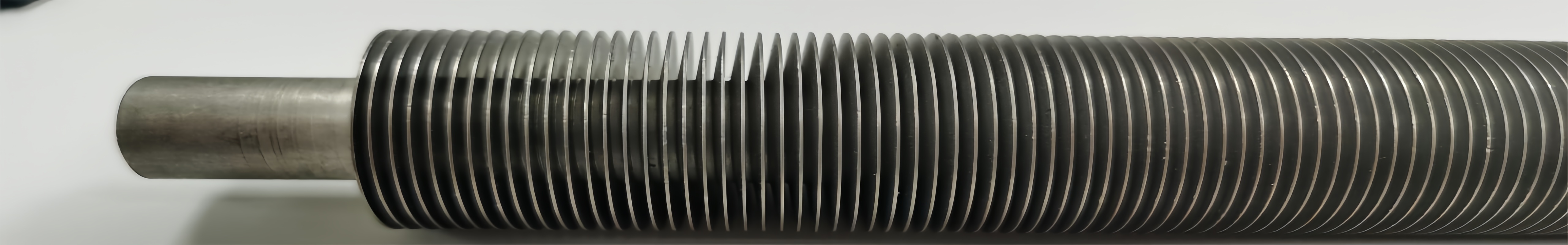

| Tube Diameter | Relatively smaller (typically Φ32–Φ51 mm) | Larger (typically Φ50–Φ76 mm) |

| Wall Thickness | Thicker walls (6–15 mm) | Thinner walls (3–6 mm) |

| Flow Path Layout | Can utilize complex multi-pass arrangements | Simplified parallel flow path designs |

| Spatial Arrangement | Often vertical, pendant configuration with dense tubes | Commonly horizontal, platent configuration with larger spacing |

3. Material Selection

Material selection is a core aspect of superheater and reheater design, based on temperature, pressure, corrosion environment, and lifecycle cost.

3.1 Material Application for Superheaters

Superheater material selection follows a safety-first principle under high temperature and pressure. Materials are typically selected in segments according to the steam temperature gradient:

- Low-Temperature Section (≤480°C): Economical low-alloy steels are used, such as 15CrMoG.

- Medium-Temperature Section (480–580°C): Better-performing alloy steels are selected, such as 12Cr1MoVG, T11, T22.

- High-Temperature Section (≥580°C): In supercritical/ultra-supercritical units, high-grade materials are essential. Ferritic/martensitic steels like T91, T92 perform well in the 590–620°C range. For temperatures exceeding 620°C, austenitic stainless steels such as TP347H, Super304H, HR3C are required.

3.2 Material Application for Reheaters

Reheater material selection reflects a techno-economic balancing strategy:

- Low-Temperature Inlet Section: Due to lower gas temperatures (typically ≤450°C), carbon steel SA-210C can be used for optimal economy.

- Medium-Temperature Section: Based on the specific temperature zone, low-alloy steels like 15CrMoG, 12Cr1MoVG, or T11 are selected.

- High-Temperature Outlet Section: In areas facing high-temperature corrosion and oxidation (gas temperature ≥550°C), similar to superheaters, materials like T91 or austenitic steels are needed. However, a key distinction is that for the same material grade, reheater tubes have a significantly reduced wall thickness, greatly lowering material usage and cost.

4. Location and Arrangement within the Boiler System

4.1 Heat Transfer Mechanism

Superheaters are typically located in the highest gas temperature zones (furnace outlet and high-temperature convection zone), receiving both radiative and convective heat transfer. In furnace outlet platent superheaters, radiative heat transfer can account for 40%–60% of the total.

Reheaters are mostly placed in the medium-temperature gas zone downstream of the superheater, where heat transfer is primarily convective. Due to their lower steam pressure, higher specific volume, and relatively smaller heat transfer coefficient, achieving the required temperature rise necessitates a larger heat exchange surface area.

4.2 Gas Pass Arrangement and Temperature Control Methods

In large boilers, superheaters and reheaters often employ a split gas pass arrangement. By adjusting the opening of gas dampers, the proportion of gas flow allocated to each heating surface can be altered, providing coarse control of reheater steam temperature.

Control Method Distinction

Superheater steam temperature is primarily controlled by attemperation (spraying desalinated water), enabling rapid and precise temperature control.

Reheater steam temperature control, in principle, avoids attemperation because the injected water does not perform work in the high-pressure cylinder and would directly reduce cycle efficiency. Therefore, control relies mainly on gas-side adjustment methods, including: gas dampers, tilting burners, and gas recirculation.

5. Operational Characteristics and Control Challenges

5.1 Load Adaptability

Superheater steam flow changes essentially linearly with boiler load, making control relatively straightforward.

Reheater steam flow depends on the operating conditions of the high-pressure turbine cylinder. Its relationship with unit load is complex, especially during sliding pressure operation or rapid load changes, where flow and pressure variations are more dramatic.

5.2 Startup and Low-Load Operation

During unit startup, the superheater requires sufficient steam flow to cool the tube walls, usually established via a bypass system.

The reheater may be in a dry state during initial startup, requiring strict control of the gas temperature rise rate. At low loads, reheater steam flow decreases significantly, easily leading to tube wall overheating.

5.3 Dynamic Response Characteristics

The superheater steam temperature system has relatively low inertia; attemperation response is rapid (typical time constant of 10–30 seconds).

The reheater steam temperature system has high inertia; gas-side adjustment methods have time constants that can reach 1–3 minutes. This difference in dynamic characteristics requires different control strategies and parameter tuning in the control system design.